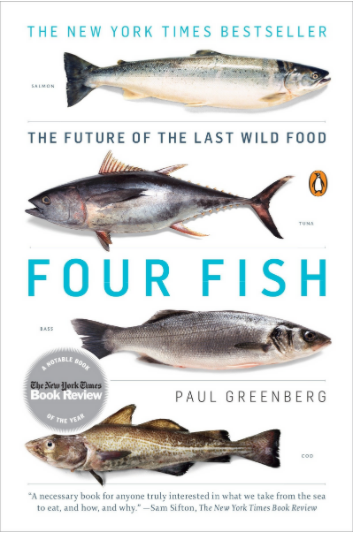

Often when we talk about seafood, we are referring to four fish that have come to dominate western seafood markets and perceptions over the last few decades. The four fish? Salmon, seabass, cod and tuna. Although the consistent supply at our grocery counter may suggest abundance of these species, there is a much larger story to be told. Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food by Paul Greenberg is a fascinating account of the history, including challenges facing aquaculture and wild populations, spikes in demand, overfishing and general perceptions, behind each of these four popular seafood species. Paul Greenberg, a lifelong fisherman and excellent storyteller, provides important context about our seafood industry and the potentially dangerous implications for the future if we continue to deplete natural resources and wild stocks by relying on our four fish of choice.

Seafood is the last wild food species that is hunted by humans. Dating back for centuries, our relationship with seafood has played an intimate role in our cultural and culinary evolution as a species. However, with recent advances in technology that have both boosted our productivity in the seafood supply and made it possible to ship worldwide, larger questions have surfaced regarding the ecological balance of our wild fish stocks and the role that human beings play in maintaining this careful balance throughout the food chain.

Salmon, seabass, cod and tuna – four fish that, through human manipulation, have become household staples for seafood eaters worldwide. Salmon, traditionally a fish for occasional consumption that, through aquaculture and selective breeding, has become widely known and consumed at the potential detriment of wild fish stocks, including fish feed. Seabass, another holiday fish whose popularity, along with advances in technology and aquaculture production, has resulted in seabass’ ubiquity in seafood markets, but demise in the wild. Cod, an everyday fish whose abundance throughout history made it an affordable staple in many households, but that has been overfished out of abundance and now teethers on fragile margins year to year. And finally, tuna, a predator that has been increasingly fished from the high seas and now falls into the endangered category for much of the fish population, with capture-based aquaculture doing little to alleviate stress on the fish.

Despite the challenges brought forth in dealing with a wild animal and how to efficiently produce seafood at mass scale, Greenberg does highlight the small victories made for each species: the rise of more sustainable aquaculture facilities, traditional fisherman going back to their roots and community adoption of local and sustainable practices. These steps in the right direction give us hope that we can correct course in our management and dependence on each of these species.

Greenberg dives into the intricacies of our human relationship with each other these fish – the dance we have done for centuries and how it has accelerated between the mid-20th century and present day to a point of trepidation. Published in 2010, Four Fish also begs the question: what is the status of each of these fish in the year 2021? For those looking to learn more about the seafood that dominates the market and how it arrives at their local grocer, Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food provides a peak behind the curtain. It is a useful resource that can help all consumers to think consciously about their seafood habits and decisions.